Abstract

Biological lifeforms can heal, grow, adapt, and reproduce -- abilities essential for sustained survival and development. In contrast, robots today are primarily monolithic machines with limited ability to self-repair, physically develop, or incorporate material from their environments. While robot minds rapidly evolve new behaviors through AI, their bodies remain closed systems, unable to systematically integrate material to grow or heal. We argue that open-ended physical adaptation is only possible when robots are designed using a small repertoire of simple modules. This allows machines to mechanically adapt by consuming parts from other machines or their surroundings and shed broken components. We demonstrate this principle on a truss modular robot platform. We show how robots can grow bigger, faster, and more capable by consuming materials from their environment and other robots. We suggest that machine metabolic processes like those demonstrated here will be an essential part of any sustained future robot ecology.

Overview

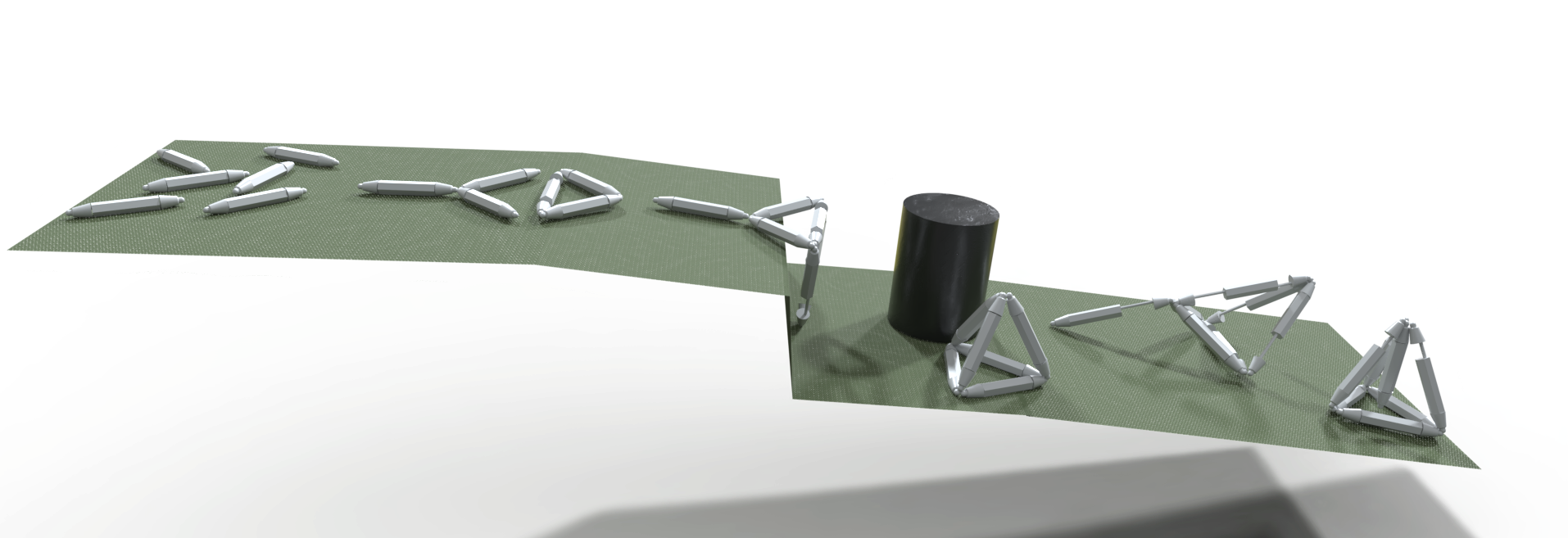

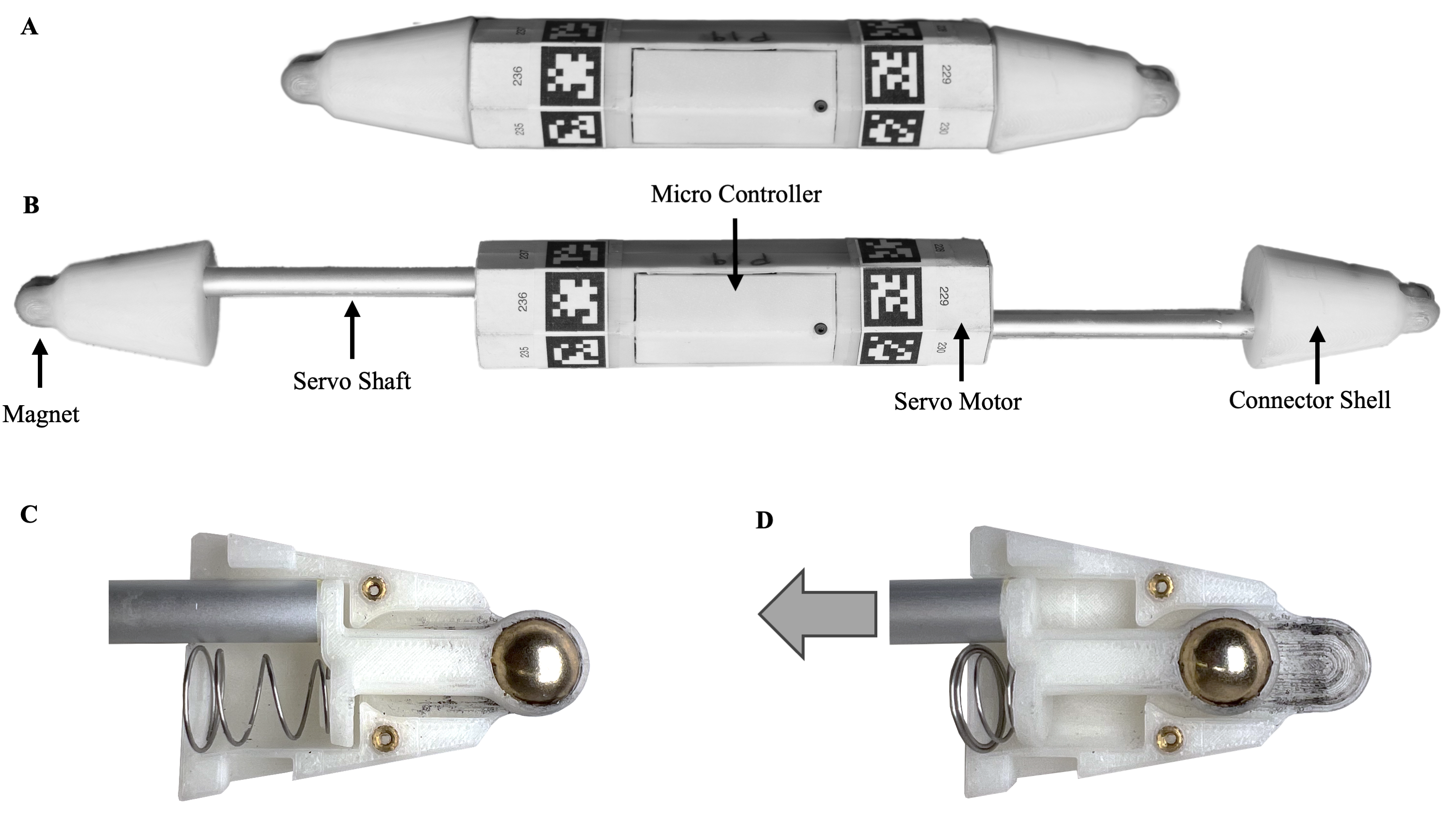

We introduce the Truss Link, a robot building block designed to enable robot metabolism. The Truss Link is a simple, expandable, and contractible, bar-shaped robot module with two free-form magnetic connectors on each end. Animating any structure, Truss Links form robotic "organisms" that can grow by integrating material from their environment or from other robots. We show how two substructures can combine to form a larger robot, how two-dimensional (2D) structures can fold into three-dimensional (3D) shapes, how robot parts can be shed and then be replaced by another found part, and how one robot can help another "grow" through assisted reconfiguration.

The concept of robot metabolism raises more questions than we can answer in this paper. Thus, we focused on a set of key challenges: self-assembly, self-improvement, recombination after separation, and robot-to-robot assisted-reconfiguration. In this work, we demonstrate the potential of this approach and introduce a robot platform capable of achieving it. We believe that this is the first demonstration of a robot system that can grow from single parts into a full 3D robot, while systematically improving its own capability in the process and without requiring external machinery.

Videos

Truss Link

Truss Links can be used to build modular robots. Modular robot systems comprise multiple parts called modules, links, or cells that can self-assemble or be assembled to achieve an objective. The Truss Link is the basic building block of our modular robot system. Modular robots promise increased versatility, configurability, scalability, resiliency and ability to self-reconfigure and evolve. Additionally, robot modularity could make robots cheaper if the modules were mass-produced. Modular robots are potentially resilient as a result of their redundancy and modularity, rather than mere material strength.

As truss robots, Truss Links form "scaffold-type" structures and have expanding and contracting prismatic joints (see Fig 2-A and B) rather than rotational ones as they are found in popular cubic-shaped models. Spherical and cubic robot models have the drawback of forming dense structures, making assembling large robots difficult. Recent developments in modular robotics have shown increased interest in both truss-style and free-form modular robots.

Results

Our results demonstrate that it is possible to form machines that can grow physically and become more capable within their lifetime by consuming and recycling material from their immediate surroundings and other machines. While these results are still nascent, they suggest a step towards a future where robots can grow, self-repair, and adapt instead of being purpose-built with the vain hope of anticipating all use cases. Robot platforms capable of robot metabolism open the door to the development of machines that can simulate their own physical development to achieve an objective and then execute that physical development. By acting as open systems, robots capable of robot metabolism bear the potential of forming self-sustaining robot ecologies that can grow, adapt, and sustain themselves, given a continued supply of robot material.

The Truss Link is the first modular truss robot capable of robot metabolism. To start, we demonstrate the Truss Link's capacity for self-assembly from individual parts—forming a three-pointed star and a triangle—and by integrating existing sub-structures—forming a diamond-with-tail from a triangle and a three-pointed star. Second, we quantify the probability of random topology formation in simulation given similar randomized initial conditions used in our physical demonstration. Third, we show how Truss Link structures can recover their morphology after separation due to impact via self-reconfiguration or self-reassembly. Fourth, we introduce a way for a ratchet tetrahedron morphology to shed a "dead" Truss Link and replace it by picking up and integrating a found link. Finally, we expand beyond the individual robot and demonstrate how a ratchet tetrahedron robot can assist a 2D arrangement of links to form a tetrahedron.

Paper

Published in Science Advances on July 16, 2025.

Code

Truss Link Hardware Repository: https://github.com/RobotMetabolism/TrussLink

Truss Link Controller (Server): https://github.com/RobotMetabolism/TrussLinkServer

Truss Link PyBullet Simulation: https://github.com/RobotMetabolism/TrussLinkSimulation

Citation

@article{

doi:10.1126/sciadv.adu6897,

author = {Philippe Martin Wyder and Riyaan Bakhda and Meiqi Zhao and Quinn A. Booth and Matthew E. Modi and Andrew Song and Simon Kang and Jiahao Wu and Priya Patel and Robert T. Kasumi and David Yi and Nihar Niraj Garg and Pranav Jhunjhunwala and Siddharth Bhutoria and Evan H. Tong and Yuhang Hu and Judah Goldfeder and Omer Mustel and Donghan Kim and Hod Lipson },

title = {Robot metabolism: Toward machines that can grow by consuming other machines},

journal = {Science Advances},

volume = {11},

number = {29},

pages = {eadu6897},

year = {2025},

doi = {10.1126/sciadv.adu6897},

URL = {https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/sciadv.adu6897},

eprint = {https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/sciadv.adu6897}

}

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSF AI Institute in Dynamic Systems, NSF NRI, and DARPA Trades for their support.

DARPA TRADES COLUM 5216104 SPONS GG012620 01 60908 HL2891 20 250

NSF NRI COLUM 5216104 SPONS GG015647 02 60908 HL2891

NSF NIAIR COLUM 5260404 SPONS GG017178 01 60908 HL2891